Critical Inquiry Critical Inquiry

Winter 2026

Volume 52 Issue 2

-

- 181–Yves Winter

What Is an Imaginary?

Over the last few decades, the neologisms social imaginary and political imaginary have become ubiquitous in the jargon of the humanities and the theoretical social sciences. And yet, despite the pervasive use, there is remarkably little convergence on what these terms mean. How have they captivated the vernacular of contemporary social, cultural, and political theory? Tracing the sources of the idiom imaginary to phenomenological studies of psychology in 1940s France to the present, this article examines two key historical junctures: the moment when imaginary morphed from an individual to a collective category in 1960s French philosophy and its translation and insertion into anglophone cultural and political theory in the 1980s and ’90s. In contemporary anglophone theory, imaginary has become a proxy for the concepts of ideology and utopia in the wake of the culturalist turn of the 1990s and 2000s. As such, the sprouting of imaginaries is inseparable from an increasingly consensual cultural idealism that dominates contemporary cultural and political theory.

-

- 204–Christopher Grobe

Botface

Evidently, people love watching others pretend to be robots. This article uncovers hidden links between this practice and blackface performance, then theorizes the two as similarly metatheatrical practices in the realm of the infrahuman. Studying the international performance and reception history of Karel Čapek’s R.U.R., the science-fiction melodrama that coined and popularized the word robot, this essay demonstrates how robot characters came to behave how they do and how this behavior blackened them in the eyes of certain audiences. Paying special attention to a repeated trope of botface performance (the scrutiny scene) the essay shows how people were taught to look with paranoid intensity at robots for signs of their failed or emergent humanity. Through close study of the play’s reception, the article shows that it was in learning to look at actors this way—especially white actors in even whiter makeup—that people came to understand robots as Black. Throughout, attention is paid to how these kinds of performance and spectatorship were, in fact, connected to key emerging ideas about acting—especially realist acting—thus suggesting a secret, racialized history for these modes of acting.

-

- 242–Robert Mitchell, Orit Halpern, and Henning Schmidgen

The Planetary Experiment: A History and Theory of Science at Scale

The article introduces and discusses the concept of planetary experimentation, its history, and its implications for understanding the relationship between humans and the environment, highlighting the need for a better understanding of knowledge production in the face of global warming and other human-driven environmental changes. We use a historical approach to understand the development of planetary experimentation, from its early phases to its current forms. In particular, we distinguish three phases of planetary experimentation: (1) geoterritorial surveying (1830s–present), exemplified by the Magnetic Crusade of the British Empire; (2) cybernetic control (1930s–present), exemplified by nuclear bomb technologies and their testing programs as well as by the postwar Green Revolution initiatives of the Rockefeller Foundation; and (3) generative management (1990s–present), exemplified by AI driven initiatives aiming at establishing Digital Twins of the Earth, such as the European Union’s Destination Earth project. Our analysis suggests that the concept of inadvertent planetary experimentation is probably not the most helpful way to approach the causes and current dynamics of the problematic global changes captured by the term Anthropocene. We argue, though, that the history and language of planetary experimentation can open up contemporary discussions of engineering and technical solutionism to a critical history of politics, truth, and aesthetics.

-

- 266–Esther Yu

The Novel as Practice of Consciousness: Locke and Defoe, Revisited

This article models a reading of the novel’s continuous prose as narrative exertion—as an effortful activity embedded in practitioners’ temporally extended doings. It treats the novel in other words as a practice, where practice is defined apart from theoretical abstraction as the concept-rich site of iterative and often tacitly knowledgeable action. The recurrence of one effortful action across early eighteenth-century fiction—first-person prose narration—invites attention as a practice thus defined. The present study traces this enduring literary practice to early modern England’s embrace of life writing: continual, regimen-based acts of writing were widely enjoined across the seventeenth century as the routine care of the conscience. The early novel draws on these practices of the conscience to cultivate a related realm, the domain of consciousness then receiving explicit philosophical definition. Defoe’s practice of prose holds together what this essay shows to be a conscience-consciousness matrix. Such a matrix reopens the perennial question of the novel’s relation to empiricism: as this essay argues, Defoe’s writing calls an emergent epistemology to account. Defoe credits Lockean empiricism with holding out world-historical promises of shared understanding. But the Lockean account of consciousness—especially in its tabula rasa state—can only describe without resolving what Defoe represents as a crisis of epistemological isolation. In the novelist’s view, the empirical promise remains empty if not dystopian without necessary collective practices, including the joint exercises of ongoing narration.

-

- 283–Saul Nelson

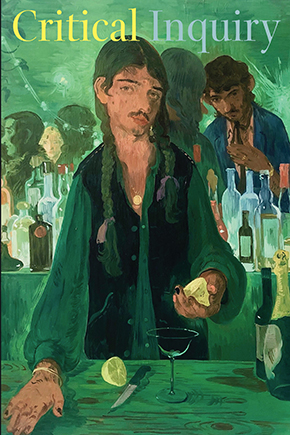

Manet and Neoliberalism: The Case of Salman Toor

Deep into its latest comeback, more obsessed than ever by its own history, contemporary painting keeps rediscovering that history in the reworked contents of modernism’s first masterworks. Compositions recur; identities change. In Salman Toor’s The Bar on East 13th (2019), the Folies-Bergère becomes a Manhattan gay bar, Édouard Manet’s barmaid an androgynous barman. Such switching of content has become so prominent a feature of contemporary painting as almost to amount to a new genre. Figurative painters are celebrated as, simultaneously, champions of identity and conservers of tradition. I argue, by contrast, that the new paradigm is fundamentally antitraditional. If Toor and his peers can’t stop coming back to Manet, this is to reaffirm, each time, the inaccessibility of pictorial values such as difficulty, reserve, and autonomy, for which his painting once stood. This is no bad thing; rather, it bespeaks a kind of painting attuned to those forces in contemporary culture—digitization, globalization, and neoliberalism—that have rendered those values illegible.

-

- 313–Colleen Ruth Rosenfeld

Supposing … : On Variation in Picasso’s Las Meninas (after Velázquez) and Shakespeare’s Sonnets

Reading Pablo Picasso’s suite of paintings, Las Meninas (after Velázquez) (1957), alongside William Shakespeare’s Sonnets (1609), this essay asks: What can Picasso’s variations on Las Meninas teach us about aesthetic form in the Renaissance that Michel Foucault did not in his charismatic reading at the opening of The Order of Things? With particular attention to Picasso’s rearrangement of the Infanta’s face, I suggest that the interlocking, double profile dismantles the Infanta’s forward-facing gaze. By eliminating the “essential void” that Foucault understood to underwrite all acts of representation, Picasso’s variations also suggest a new model for literary criticism, one which uses supposition as a method of reading. Through acts of supposing and the variations such acts produce, literary criticism might attend to the contingency of form and a poem’s latent capacity to be otherwise. I argue that, when viewed from the angles of vision supplied by Picasso’s variations, an aesthetic feature of Shakespeare’s Sonnets traditionally called “vagueness,” “imprecision,” or “uncertainty” snaps into focus as the sonnets’ capacity to shelter their own variations, and I argue that an adequate criticism describes the fullness of this capacity.

-

- 341–James I. Porter

When Is Philology Made Jewish? The Example of Erich Auerbach, Part 1

The first part of an examination of Erich Auerbach’s philological method in connection with his Jewish background. The article takes issue with quite recent Christianizing approaches to Auerbach, including those that attempt to demonstrate how Catholic and Protestant theology influenced his writings, in particular that of Rudolf Bultmann, his contemporary at Marburg. Philology made Jewish names a style and approach to literary history that counters antisemitism and anti-Judaism. Auerbach is an exemplary figure but hardly unique. The article is a first step towards a larger project about the modern extensions of philology beyond its conventional academic uses—philology in dark times, philology in exile.

-

- 363–Michael Dango

Taxonomic Criticism

While advocacy of literary criticism often singles out close reading, this essay argues that a more important skill that enables formalism in the first place is taxonomy—dividing, categorizing, and mapping the cultural field by means other than, say, Amazon’s algorithms that tell us if we like x we should also buy y. Taxonomy is a skill of aesthetic judgment, exploring the dialectic between object and category, and although the paradigmatic category is the beautiful (and related evaluative categories like good art), the skill can, and should be, directed to a wider set of categories, including ones we are prompted to invent and name by the objects we study. This categorical approach traces back less to the New Critics and more to the Neo- Aristotelian Critics affiliated with the University of Chicago. This essay recovers their approach to genre and goes on to argue that it came closest to being perfected in a succeeding generation by radical feminists, whose politicization of rape in the 1970s was fundamentally a project of literary criticism. Intervening into recent debates on the politics of aesthetic education, I argue that apprehension of an aesthetic field of categories depends on a prior apprehension of a political field of categories, which for radical feminists included what harms belonged to categories such as rape or what subjects were paradigmatic of categories such as survivor. Approaching political categories with the aesthetic skill of taxonomy, I ultimately recommend politics as an exercise in genre criticism.