Critical Inquiry Critical Inquiry

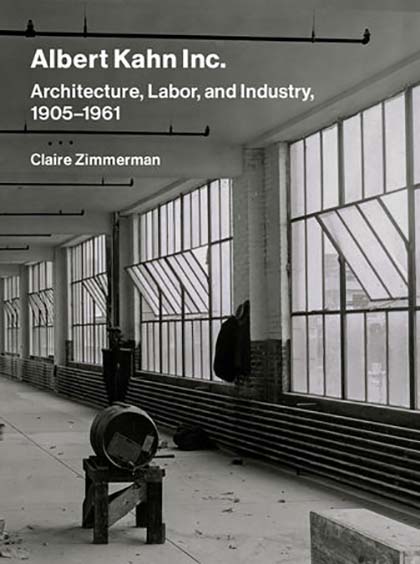

Claire Zimmerman. Albert Kahn Inc.: Architecture, Labor, and Industry, 1905–1961. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2025. 488 pp.

Review by Jacobé Huet

7 November 2025

Some books in architectural history rival the monumentality of buildings themselves. Claire Zimmerman’s Albert Kahn Inc.: Architecture, Labor, and Industry, 1905–1961 is one such case. It evokes monumentality not only in its physical heft but in its landmark contribution to the field, offering what Zimmerman describes as an “alternative history of modern architecture that redirects attention to the masses of buildings that underpinned American empire, but that remained often unaccounted for in accounts of twentieth-century architecture” (p. xix). The author develops her narrative through a series of thematic chapters, beginning with biographical insights into the family business, moving into its historical context, and continuing with considerations of planning, construction, and ultimately, occupancy. From here, one might ask whether Zimmerman’s book re-monumentalizes Albert Kahn’s factories, hangars, and plants, buildings that once functioned as monuments to capitalism, signaling it on a grand scale but, as she convincingly shows, consistently neglected by mainstream architectural history. The kind of discursive monumentalizing the book performs is critical and reflective rather than self-aggrandizing, memorializing a defunct yet still painfully resonant phase of capitalism.

What counts as “alternative” in “alternative history” is, of course, highly disputed, raising the question of whether the book ultimately unsettles or reinforces established narratives in architectural history. The issue is especially pertinent given that the book is far from the first monograph on Kahn. Zimmerman cites seven prior book-length studies early in her introduction. However, the author presents her book as the first to locate Kahn’s work intentionally and systematically within its ideological nexus, centered on capitalism. This position induces a distinctive scale for the inquiry, one that is both fluctuating and productive. It’s not just a book on Kahn—although he remains the principal figure—nor just on the collaborators in his firm. It certainly is a book about Detroit, where the firm was based and left the most visible mark, but not only about Detroit, because Albert Kahn Inc. operated globally (I recommend that readers linger on the striking world map in the preface). At times, the book extends claims on architecture and capitalism as a whole, beyond narrow definitions of places and protagonists. Though especially germane to Americanists, the book’s shifting scale ensures its acute relevance to broad audiences, including all who study architecture as a locus of power and ideology.