Critical Inquiry Critical Inquiry

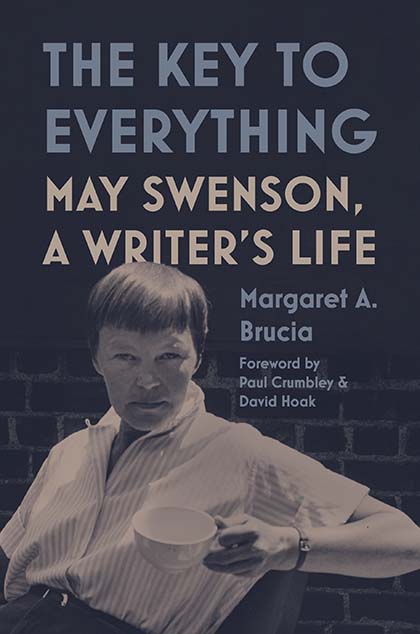

Margaret A. Brucia. The Key to Everything: May Swenson, A Writer’s Life. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2025. 263 pp.

Review by Lucky Issar

23 October 2025

May Swenson emerges vividly in Margaret A. Brucia’s biography, The Key to Everything, which highlights the poet's lifelong pursuit of words and meaning making. Brucia implicitly underscores Swenson's fascinating, humbling, and unconventional approach to her writing and literary career. Throughout, Swenson regarded the very act of writing as the most authentic measure of accomplishment. Unlike other celebrity women writers of the twentieth century, such as Gertrude Stein, Sylvia Plath, Susan Sontag, Adrienne Rich, or Erica Jong, Swenson’s work reached its audience less through spectacle or nonliterary events than through gradual accumulation. Even the seemingly mundane events of her life, as documented in the biography, surface as her poems do—most poignantly her quiet death in her idyllic village home “overlooking Hampstead Harbour of the north shore of Long Island,” framed as a singular, embodied form seamlessly transitioning into a realm of intangible, disembodied forms (p. 211).

Instead of romanticizing hardship or dramatizing her life, Brucia presents Swenson as a writer defined by resilience and intelligence. Raised in a religious Mormon household in the early twentieth century, Swenson navigated the challenges of growing up queer on her own terms. Although her radical pursuit of form and meaning as a queer poet led her to move to New York, she nevertheless maintained close relationships with her siblings and parents throughout her life. Even readers unfamiliar with Swenson’s work can appreciate both her poetic sensibility and the grounded quality of her everyday life. Recognition of her work eventually came through readership, awards, and critical appreciation, but the most striking aspect of her life remains her unwavering devotion to poetry. Swenson’s Swedish heritage, her family’s migration story, her early life in Utah, her sexuality, her “European journey,” her female relationships—including her decades-long literary friendship with poet Elizabeth Bishop—and her life in New York, which she considered her “home town,” are all captivating, yet none is as engrossing or central as her vocation (pp. 187, 47). The biography, though it gestures toward structural inequities in the publishing world—particularly those limiting writers marginalized by gender and sexuality—demonstrates that such setbacks rarely influenced Swenson, who chose to frame her life not in terms of complaint or resistance but through absolute commitment to her art.

In 2025, several biographies of influential twentieth-century women writers have been published, many of whom identified themselves as feminist or queer, such as The Power of Adrienne Rich by Hilary Holladay. Rich's biography offers an instructive counterpoint to Brucia’s work on Swenson, even illuminating it. Profoundly devoted to the written word, both writers share striking continuities but also decisive divergences in negotiating life and poetry. Swenson, who came from a modest background, pursued her literary interests without any active guidance, though her father “encouraged” her to write diaries (p. 20). By contrast, Rich was actively steered toward scholarly pursuits by her father, a formidable intellectual who cultivated his daughter's talent from early on. Unlike Swenson, who grew up in a kind of literary backwater and “a bubble of Mormonism,” Rich received a polished education and benefited from advantageous social and literary connections, given her background (p. 17). Although both gained prominence as poets, neither the provincial father in Swenson’s case nor the exacting, intellectual father in Rich’s provided ease of passage. As queer women, they faced challenges both in the publishing world and in broader male-dominated society. Whereas Swenson’s corpus unfolds as the sustained expression of a unified sensibility rooted in an all-consuming desire to be a poet, Rich’s literary and personal pathways were marked by turbulence—a continual reshaping of identity and voice that, though bold, could be interpreted as inauthentic or self-serving. Despite Rich being known as a celebrity-activist author in her own time, Swenson’s work and life in retrospect seem more vital, relevant, and resilient than Rich’s.

Reading Swenson’s life alongside other recent biographies highlights her distinctiveness as both poet and individual without minimizing the difficult conditions under which these women writers worked. Brucia’s biography reintroduces to the present-day reader the life and work of a poet who may not have glittered like her contemporaries but embodies a mine of poetic elegance and subtlety. Situating Swenson centrally within the realm of poetic creation and aesthetic, Brucia's biography echoes her subject’s coherence and linguistic precision.