Critical Inquiry Critical Inquiry

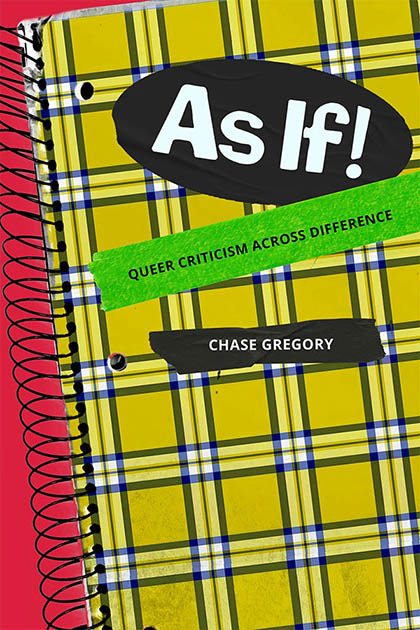

Chase Gregory. As If!: Queer Criticism Across Difference. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2025. 200 pp.

Review by Patrick Kindig

30 January 2026

Today, queer studies scholars face a choice: work with identity or work against it. Practitioners can embrace conventional categories of race, gender, and sexuality as politically useful (as thinkers such as Audre Lorde did), or, like Leo Bersani, they can treat the very idea of coherent identity as epistemically and ethically suspect. Rarely does a scholar find a way to circumvent such zero-sum thinking, but Chase Gregory’s As If! does just this.

Without completely doing away with the concept of identity, Gregory calls into question the idea that “stable political identities” are necessary to the cohesion of “identity knowledge” fields such as queer studies; more importantly, they critique the assumption that such identities can only be theorized from within (that is, by scholars who inhabit said identities in everyday life) (p. 3). Drawing attention to the practices of critical cross identification that characterized much early queer theory—think, for example, of Eve Sedgwick’s famous identification with gay men—they suggest that these practices might offer us a more nuanced way to think about selfhood. To make their argument, they turn to the work of four literary critics aligned with queer thought in the 1990s—Deborah McDowell, Barbara Johnson, Robert Reid-Pharr, and Sedgwick herself—and isolate moments in which these critics neither discard the logic of identity wholesale nor take the boundaries of identity for granted, moments in which, rather, they try to identify across difference. These moments exemplify a kind of criticism that Gregory terms “as if!” criticism, a mode of writing in which an author attempts, often in messy, complicated, self-conscious, ironic, and even camp ways, to write “as if” they occupied a different subject position. Ultimately, Gregory suggests, this mode of criticism might provide us with a model for contemporary queer-theoretical scholarship, for rather than link “knowledge to identity in ways that delimit how theory is produced, valued, and read,” “as if!” criticism helps to account for (and even celebrates) identification’s unpredictable, queer swerves (p. 3).

Gregory’s argument is both gratifyingly clear and disciplinarily refreshing, as it theorizes queer selfhood in terms that fall somewhere between rigid essentialism and postmodern flux. Crucially, it does so by turning to the intellectual habits of literary criticism, a field that, in a “world where academic scholarship is increasingly being funded insofar as it has deliverable sociological correlates,” has fallen somewhat out of favor in queer studies (p. 4). This thrust of Gregory’s argument, though perhaps not central, is important, for social theory may aptly describe and explain what is, but it is in the imaginative realm of the aesthetic that we are able to speculate about what might be. Not only, then, is it appropriate that Gregory should turn to literary criticism to theorize those modes of conditional identification that characterize “as if!” criticism; it is precisely this turn to the literary-critical that provides us with a roadmap—however incomplete or provisional—that we might use to navigate the future of queer studies.