Critical Inquiry Critical Inquiry

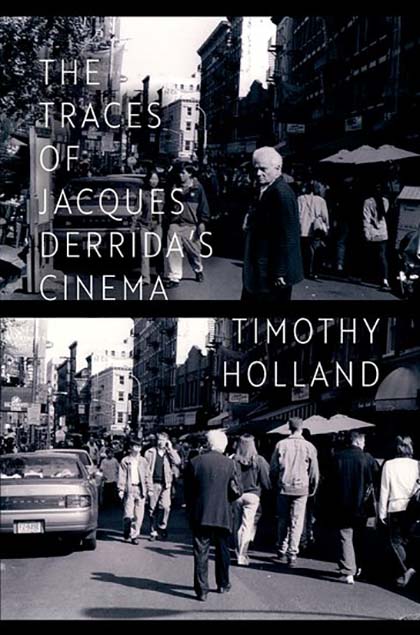

Timothy Holland. The Traces of Jacques Derrida’s Cinema. New York: Oxford University Press, 2024. 280 pp.

Review by Erin Graff Zivin

9 October 2025

At times it seems that there is no topic about which philosopher Jacques Derrida did not write: from Plato to contemporary politics, marranismo to monolinguism, his mother to his feline companions, the deconstructive thinker did not shy away from objects of study and thought that might eschew his area of formal training. Aesthetics figured prominently in his oeuvre, but while artistic forms such as narrative, photography, painting, and architecture found a place in his writings and lectures, Derrida shied away from two: music and film.

In The Traces of Jacques Derrida’s Cinema, film theorist Timothy Holland tackles the latter. An impossible task: excavating and imagining the largely oblique, subterranean relation between the discipline of film studies and the vast oeuvre of the deconstructive thinker. For Derrida, cinema was a dangerous experience (the Latin per- of experience being key here) and, as Holland points out in his impressive excavation of the archives, Derrida did not want to sacrifice or stain his own experience as a cinematic spectator. It was as if the pleasure, the state of belief in nonbelief, the suspension of reason—elements that, in principle, did not contradict his philosophical ideas—could not withstand the labor of thought.

It is not without irony that Holland chooses to refer to “Derrida’s Cinema” in the possessive, as if cinema were something that could be proper to Derrida, or to anyone at all. In the first chapter (“Ses fantômes”), Holland identifies a similar ambivalence in the possessive “its” of “Cinema and Its Ghosts,” the title of Derrida’s interview with Cahiers du cinéma). Such possession, if it will have been, is possible only as trace, a haunting absent presence. The chapter surveys work by and about Derrida and film in order to demonstrate the scarcity of deconstructive work in the discipline of cinema studies, as well as the ambivalent place of cinema in Derrida’s writing. Despite a certain scarcity of writing on the topic, Holland argues, film haunts Derrida’s thought, and the films that feature Derrida likewise exhibit a spectral thread.

Chapter 2 (“Believing Without Believing”) pursues this spectral thread through a close reading of Derrida’s response to Pascale Ogier’s question “Do you believe in ghosts?” in the film Ghost Dance–a filmic scene that haunts Derrida after Ogier’s death. The interview–and Holland’s reading of it–interests me because in it lies a possible key to understanding Derrida’s resistance to writing about both film and music: the question of improvisation. In this and other filmed interviews, improvisation appears as something that both fascinates and terrifies Derrida, both performatively and constatively, and Holland is one of the few scholars to take on this crucial theme. (Elsewhere, David Wills has written beautifully on the improvised encounter between Derrida and Ornette Coleman.)

In the third chapter, “Inhabitations (Derrida and David Lynch),” the author performs the kind of work that he claims is lacking in cinema studies: a serious, deconstructive (blind?) reading of Lynch’s films. Finally, chapter 4 (“Il faut vraiment lui laisser ça: The Remains and Solicitations of Cinema”) turns to the institution of the university to attend to Derrida’s nonprescriptive assertion that cinema “be left to remain” (p. 168). Throughout, Holland strikes a balance between responsible scholarship that surveys the relevant literature (in this, it is very much a first book) and risky, speculative thought that opens towards possible futures.

One could argue that Holland’s linking of Derrida with film is itself a kind of improvisation: he proceeds with no predetermined program, no entrenched scholarship to guide the way. In this sense, Holland’s book stands as a model for scholarship at a time in which the conditions of possibility for thought are growing narrower and more elusive. In the wake of humanities and the university, then, Holland’s books conjures and invites more (blind) cinema, more (deconstructive) reading, more (ghostly) improvisation.